The Three Layers of Skin and How They Function

Human skin is wildly misunderstood. On a basic level, we all know it protects our bodies from outside assaults.

Have you ever wondered how a wound heals, why our skin sheds so frequently, and how our bodies stay warm? These are just a few mysterious ways our skin does what it does.

But, what even is the skin, and how does it work? Here, you'll find out how each layer of skin functions and how they use cellular components to communicate with each other and the body as a whole.

How many layers of skin are there?

The skin is the largest organ of the human body, making up a total area of about 20 square feet and roughly 8 pounds in weight for adults.

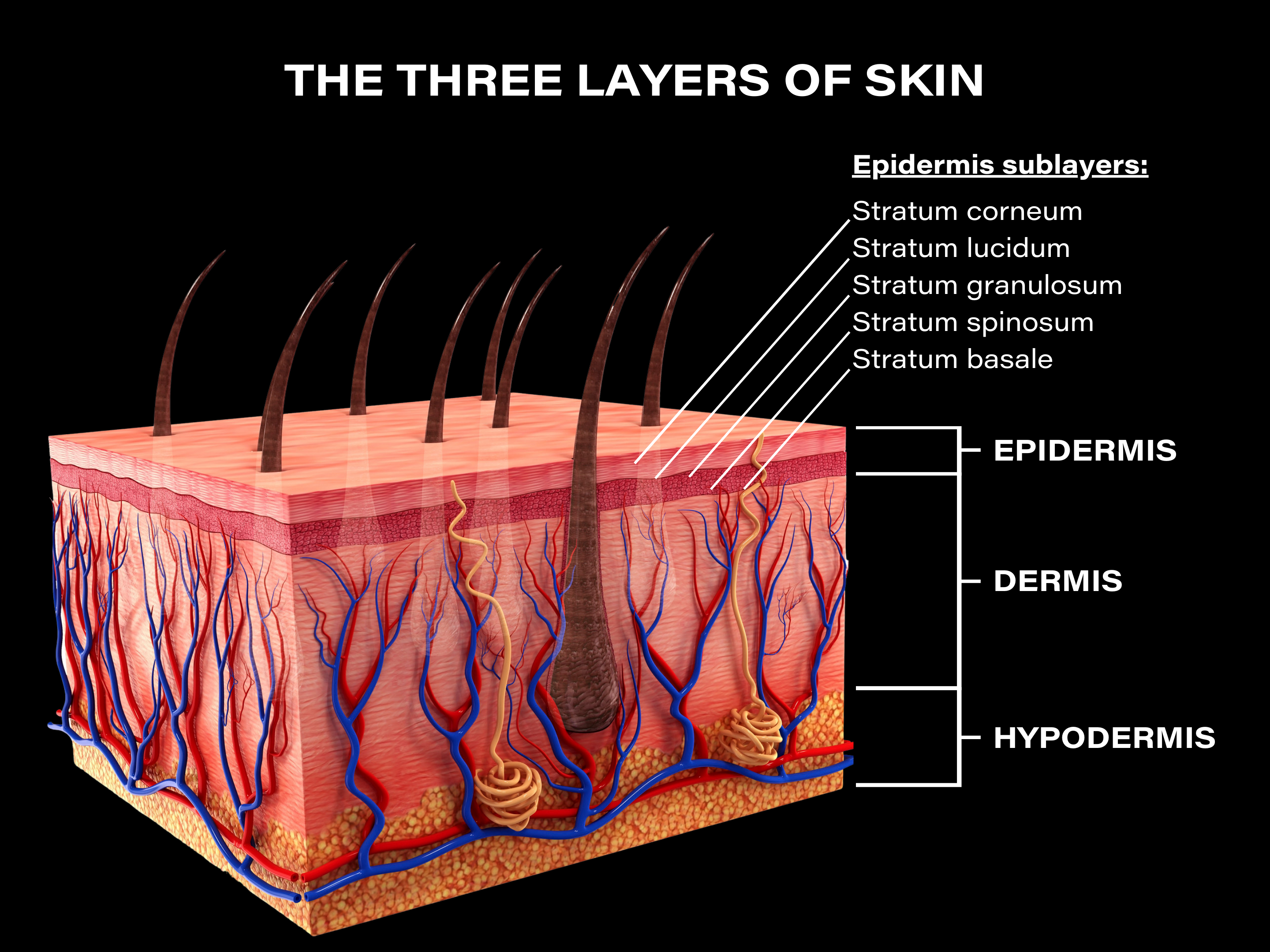

Humans have a total of 3 main skin layers. Each layer is complex, and numerous other "sublayers" exist which all serve important functions.

The 3 main layers of skin in order include:

- Epidermis (outer layer)

- Dermis (middle layer)

- Hypodermis (deepest layer)

While we might think the skin as a whole is rather simple, all three layers are completely distinct in their function and anatomy.

The three layers of skin and their functions

Why might we care about the different layers of skin?

They make up an intricate network, where they deeply intercommunicate and serve numerous critical functions.

Everything from skin hydration and hair growth, to sensations of touch and differing temperatures, and even to the development of chronic skin diseases, are all because of each skin layer.

1. Epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost layer of skin and the layer we see with our eyes.

While the epidermis is by far the thinnest of the three layers of skin, it acts as a complex system and plays a major role in communicating and influencing the body's immune system for defence purposes.

It provides a barrier from the outside world, defending against harmful foreign substances and pathogens from entering the deeper layers of skin and our body's bloodstream. It also does a good job at retaining water and important nutrients in the skin.

The thickness of the epidermis varies across the body, and is the thickest on the palms of hands and soles of feet for added protection.

It doesn't contain its own blood supply, which is why our skin can be shaved or scratched without bleeding.

Here are the main functions of the epidermis:

- Protects the body: it acts as a tough barrier or "brick wall" from the outside world through a number of different mechanisms, protecting against pathogenic invaders, sun exposure, chemicals, and abrasions. In fact, its strong protection ability is the reason why most skincare products don't penetrate deep into the skin.

- Maintains skin hydration: the epidermis is largely lipid (oil) based, and it creates a waterproof barrier which moisturizes and prevents water loss.

- Cell renewal: it has a natural exfoliating process whereby cells known as keratinocytes are formed at the bottom of the epidermis, and travel to the surface where they die and flake off of the skin. This is a continuous process important for cell renewal in order to keep the skin in good condition.

- Gives skin its color: a type of cell called melanocytes produce the pigment melanin, which gives skin its color.

The five sublayers of the epidermis

The epidermis is actually made up of a collection of 4-5 sublayers, which include (from the lowest part to the outermost layer of the epidermis):

- Stratum basale

- Stratum spinosum

- Stratum granulosum

- Stratum lucidum (found only on certain parts of the body)

- Stratum corneum

Stratum basale

Stratum basale is the deepest layer of the epidermis and is made up of a single layer of cells (yes, it's tiny), with the main proportion being basal cells.

This layers rests on top of a thin protein layer known as the basement membrane, which forms the "floor" of the epidermis, connecting stratum basale and the epidermis with the dermis.

You can think of the stratum basale as a factory, where its main function is to produce new cells. Specifically, basal cells are responsible for producing a type of cell known as keratinocytes, which I'll be talking a lot about in this article.

Stratum basal continuously produces keratinocytes, which then move to the outer layer of skin. You may have heard of them before, as they're skin cells that make up about 90% of the cells in the epidermis.

Keratinocytes are cells that produce lipids which function as a protective barrier for skin, as well as keratin—a structural and protective protein that makes up skin, hair, and nails.

They're also important for the formation of Vitamin D when exposed to the sun.

Melanin-producing melanocytes can be found here as well, consisting of up to 25% of the cells here.

Stratum spinosum

Stratum spinosum is the sublayer positioned right on top of stratum basale, and is 8-10 cell layers thick. It comprises most of the epidermis.

The keratinocytes in this sublayer are irregularly shaped and joined together with desmosomes—protein complexes that provide strong adhesion between cells.

Desmosomes play a role in maintaining the structural integrity of skin.

Langerhans cells are in abundance in the stratum spinosum, scattered amongst the keratinocytes. They act as first line defenders, protecting against pathogenic microorganisms and damaged cells.

In this layer, keratinocytes start to produce keratin and create a barrier to prevent water loss.

Stratum granulosum

Stratum granulosum is a thin layer that contains keratinocytes—which are specifically known as granular cells in this layer (hence the name, granulosum).

Skin cells in this layer start to die in order to form a tough waterproof barrier on the surface of the skin, in a process known as keratinization.

Granular cells bind these dead cells together, forming a protective barrier from the body and the outside world.

Stratum lucidum

Stratum lucidum is a thin layer that gives skin the ability to stretch, and also contains a keratin precursor which causes the degeneration of skin cells.

This layer lessens the effects of friction in the skin, and It's only found in thick areas of the body like the palms and soles of the feet.

Stratum corneum

Stratum corneum is probably the most famous of the 5 sublayers, due to its effects on overall skin health.

It's the outermost sublayer of skin, and comprised of dead cells contained in a lipid matrix. Once thought to be nothing more than a layer of dead cells, It's now known that it serves critical biological functions for the skin.

Here, keratinocytes are turned into corneocytes—dying and dead cells which make up the majority of the stratum corneum.

Lipid bilayers comprised of cholesterol, ceramides, and fatty acids surround the corneocytes, where they form a tough brick-and-mortar structure.

This is why the stratum corneum is sometimes referred to as a brick wall, as it functions to provide a tough barrier from the outside world, and protect the deeper layers of skin from pathogenic invasion and water loss.

Desquamation in the stratum corneum

On the surface of the stratum corneum, the final act of keratinization occurs known as desquamation, where corneocytes shed, or exfoliate, off of the skin.

Once keratinocytes are changed into corneocytes, they shed within about a 2-week period. As this happens, they're continuously replaced by newly formed corneocytes from deeper epidermal layers.

Desquamation is an important natural cycle of renewal for the skin, which keeps it in good condition.

Did you know that dust found in homes is mainly just dead skin cells? Gross, I know, but this is all thanks to desquamation.

The lipid bilayers in the stratum corneum

The lipid matrix is thin and made up of two layers of lipid molecules, which are specifically known as lipid bilayers.

The lipid bilayers make up the skin's barrier function—playing a major role in keeping the skin moisturized, and preventing TEWL (trans-epidermal water loss) and invasion of external pathogens.

Sebaceous glands which stem from the dermis produce an oily-waxy substance called sebum, which is released and coats the surface of the skin.

Sebum is what makes up the majority of the lipid bilayers, while keratinocyte-secreted lipids make up a minor part of the lipid bilayers.

While they're comprised of cholesterol, ceramides, fatty acids, and phospholipids, fatty acids are of particular interest when it comes to a healthy functioning skin barrier.

The reason for this is because a certain portion of the fatty acids in sebum are omega-3 and 6 essential fatty acids, meaning we need to get them through our diet as our bodies can't naturally produce them.

When our bodies can't naturally produce these essential fatty acids, we end up with irregular sebum composition and oil production—creating the baseline to developing many different chronic inflammatory skin diseases.

As a major essential fatty acid in the skin's sebum, linoleic acid in particular, is one of the most critical nutrients for the skin's barrier function. Its deficiency is super common, and when this happens, the skin responds by overproducing a non-essential fatty acid called oleic acid.

Excess oleic acid is proven to be detrimental to the skin's barrier function, and is a common link between inflammatory diseases like acne, psoriasis, and eczema.

The microscopic layer: the skin microbiome

Okay, the skin microbiome isn't technically a layer of skin, but it does live on top of the surface of the epidermis.

Residing on the top of the stratum corneum and inside hair follicles, the skin microbiome is a massive colony of 1.5 trillion microorganisms (with a T) including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and mites (yes, mite-like creatures).

Known as skin flora, they're deeply interconnected with the skin where they serve pivotal roles in its overall health.

They communicate with our immune system, and work to defend against pathogens and injury.

Skin flora have anti-inflammatory benefits, helping to prevent skin diseases and repair wounds.

Epidermis cells

The main types of cells that make up the epidermis are keratinocytes, melanocytes, langerhans cells, and merkel cells.

Here's what the important cells of the epidermis do:

Keratinocytes

Keratinocytes make up about 90% of the cells in the epidermis.

They produce keratin—structural and protective protein that makes up skin, hair, and nails. Therefore, keratinocytes have a structural role, and also form tight bonds with other cells.

As previously mentioned, keratinocytes go through a process known as keratinization. They're formed in the stratum basale, where they migrate outwards until they're eventually turned into corneocytes (dead and dying cells) and exfoliated off of the skin from the stratum corneum.

Throughout this process, however, they produce a number of important components of skin. The first of course being keratin, but also cytokines which trigger immune responses and inflammation, and growth factors.

Keratinocytes are important for protecting the body against foreign substances, as well as moisture and heat loss.

They're also essential in restoring the epidermis after injury and for successful wound closure. When a wound is formed, keratinocytes migrate to the area where they rapidly multiply to fill it. This is specifically known as re-epithelialization.

Melanocytes

Melanocytes are a type of cell that produces and contains melanin—the pigment responsible for creating the color of skin and hair.

What melanin is less known for is that it helps protect other epidermal cells from UV (ultraviolet) damage caused by sun exposure, especially keratinocytes.

So, It's an incredibly helpful friend.

Langerhans cells

We rarely hear of langerhans cells in daily life, but in reality, they're highly important to our skin—and really, our bodies.

They're a type of dendritic cell (immune system cell) present in all layers of the epidermis, and especially concentrated in the stratum spinosum.

Langerhans cells serve as the first line of defence in the skin's immune system.

Often referred to as immune system sentinels, they work as a guard for the skin immune system and are responsible for creating reactions in the skin when they encounter pathogens and other dangers.

They constantly monitor the skin, crosstalking with the epidermal environment and determining what kind of immune response will be given when they come into contact with foreign substances.

Based on the level of "danger" that the langerhans cells come across, they will either prevent unnecessary immune activation or will signal to T cells (immune system white blood cells) to create an immune response.

Essentially, langerhans cells protect us from harm. If you get some type of injury like a cut or are exposed to a harmful chemical, langerhans cells will go to work and contact the immune system to start treating the issue.

The immune system will then send an army of inflammatory cells to the affected area, where they will either form scar tissue to prevent infection or stimulate an allergic reaction to fight the foreign substance or pathogen.

Merkel cells

Merkel cells can be found in the stratum basale, and are still not fully understood.

What we do know is that they function as light touch receptors, sending information like pressure and texture sensations to the brain via the stimulation of sensory nerves.

While they're present in varying levels all over the body, merkel cells are especially concentrated on the face, lips, hands, and feet.

2. Dermis

The dermis is the middle layer of skin, positioned in between the epidermis and the deepest layer of skin—the hypodermis, which I'll get into more below.

The dermis is largely fibrous, and while its size varies across the body, It's significantly thicker than the epidermis.

It contains an incredible amount of important skin components, which includes: hair follicles, oil and sweat-producing glands, blood and lymphatic vessels, numerous nerve endings, and tough connective tissue composed of elastin and collagen.

Okay, I know that's a lot. But what do all of these things actually do?

Here are the main functions of the dermis:

- Produces sweat: sweat glands can be found here, and they release sweat through the pores on our skin via small tubes.

- It helps us feel and touch: nerve endings in the dermis send signals to our brain which lets us know when we've hurt ourselves, when we feel an itch, or when we simply touch something.

- Regulates body temperature: the skin acts as a thermostat. Blood vessels in the dermis constrict when exposed to cold environments, retaining body heat. When exposed to heat, blood vessels enlarge so blood can circulate, allowing heat to be released to cool the body down. Sweat glands present in the dermis also keeps our bodies cool in response to heat.

- Produces oil: sebum-producing (oil, waxy substance) sebaceous glands originate here which moisturize and waterproof the skin, and are found especially concentrated on the face. Due to a number of different dietary, lifestyle, and genetic factors, overproduction of sebum can occur, leading to breakouts, oily skin, and even play a pivotal role in acne development.

- Hair growth: hair follicles originate in the dermis where they protrude through the epidermis, allowing hair to grow.

- Supplies nutrients to the skin: blood vessels in this layer acts as a transport system, providing both the dermis and epidermis with fresh blood, oxygen, and nutrients. It also eliminates waste products.

The dermis is mainly made up of a crucial fibrous structural support system called the Extracellular Matrix (ECM).

The ECM contains a high amount of collagen and elastin fibers, surrounded by a group of water-binding substances known as glycosaminoglycans.

The Extracellular Matrix components

Before diving into the layers of the dermis, It's important to know about the ECM and its components, as they're vital to the healthy functioning of the dermis as a whole.

The ECM is a gel-like matrix consisting of glycosaminoglycans, collagen, elastin, and water, which makes up most of the dermis.

Not only does it provide the mechanical and structural support of skin as you'll find out below, but it also regulates cellular function, provides a transport system for nutrients and waste products, and plays a key role in wound healing.

- Collagen

Collagen is one of the most recognized components of human skin, and It's fibrous in nature.

We all have it, and we all want more of it. It's the reason why us humans are obsessed with retinol and vitamin C serums—to stimulate collagen production in the skin.

Collagen is also one of the main reasons why we use daily SPF, in order to protect it from degrading in our skin.

To understand the importance of collagen, it accounts for a staggering 70-80% of the dry weight of human skin and is largely responsible for giving the dermis (and the skin as a whole) its structural integrity.

It's a type of protein which makes up the majority of the ECM components. There are many different kinds of collagen, but type I is the most abundant.

Collagen fibers form a tightly packed, tough cross-linked network which provides structure, strength and firmness to the skin.

What this means, is it helps keeps our skin youthful, tight, and wrinkle-free. As we age, our bodies produce less collagen, leading to wrinkle formation and dryness.

Aka, collagen is our anti-aging god.

- Elastin

Another important, but lesser known protein is elastin.

Elastic fibers, while only a minor component of the dermis, are critical for providing elasticity to the skin.

As we age, the decline in elastin is responsible for sagging skin. Since it provides elasticity, our skin becomes less able to "bounce back" into its original tight shape.

- Glycosaminoglycans

Glycosaminoglycans, or GAGs for short, are polysaccharides (carbohydrates), which are water-binding substances that help to cushion cells in the ECM.

GAGs help to fill the space in between collagen and elastin fibers. This is known as ground substance, as it literally creates a stable foundation for other ECM components.

Hyaluronic acid is one of the most common glycosaminoglycans, and one of the main components of the ECM, which is excellent for attracting water.

This is why we want our skincare to penetrate as deep as possible, as getting actives inter the dermis to work on these specific structural components is important for preventing aging skin.

The two sublayers of the dermis

The dermis is made up of two sublayers, which include:

- Reticular layer

- Papillary layer

Reticular layer

The reticular layer is the deepest part of the dermis, and connects to the third and deepest layer of skin—the hypodermis.

This layer is made of thick collagen and elastin fibers, and this makes it largely responsible for providing the bulk of the structure and elasticity of the dermis.

Asides from this, the reticular layer also supports important components like sweat glands, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands. Sebaceous glands are usually attached to hair follicles where they secrete sebum. Nerves and blood vessels can also be found here.

Papillary layer

The papillary layer is the uppermost layer of the dermis, and is of course closely connected with the epidermis.

The collagen and elastin fibers in this layer are thin and loose. It contains a thin and robust vascular system which includes both blood and lymphatic vessels, as well as sensory nerve endings and touch receptors which gives us our sense of touch.

Through its vascular system, it helps to regulate our skin's temperature and supply nutrients to the epidermis in order to produce keratinocytes.

Dermis cells

There are many different types of cells in the dermis, and they play important roles in maintaining its function.

Here's what the important cells of the dermis do:

Fibroblasts

Fibroblasts are the most abundant cells in the dermis. One of their most important functions is that they're responsible for creating collagen and the other ECM components.

The activity of fibroblasts declines as we age, which reduces the production of hyaluronic acid, collagen, and elastin. As these important ECM components are depleted, we see skin alterations like wrinkles, sagging, and dry skin.

Essentially, fibroblasts serve an essential role in keeping our skin both youthful and hydrated.

Fibroblasts also cross-talk with keratinocytes and immune cells, and together, they're highly important for maintaining skin homeostasis (a healthy state) and for wound closure.

Macrophages

Macrophages are the most common skin immune cells, and help to maintain skin homeostasis.

They're responsible for creating and eliminating inflammation. They also "eat" and kill invading microorganisms, help with wound repair, and remove dead cells.

Langerhans cells are actually a type of macrophage, which operate within the epidermis, while the macrophages here are known as dermal macrophages.

Mast cells

Mast cells are another type of immune cell, which can be found concentrated in the dermis, specifically around small blood vessels.

They contain histamine, and play a key role in allergic reactions.

Schwann cells

First described in 1973 as "a cell that looked like an octopus in the skin", little has been known about how schwann cells function.

Very recently, It’s been discovered that schwann cells form a web-like mesh (hence, its octopus shape) and wrap around nerve endings in the dermis where they intercommunicate and act as key players in pain sensation.

In fact, these cells work by a process known as nociception – which essentially means they act as pain receptors, activating nerve endings to send messages to the brain when we come into contact with harmful things like certain chemicals, or extreme temperature or pressure changes.

On top of this, schwann cells improve dermal wound healing and have a complimentary role in helping to repair nerve damage.

3. Hypodermis

The hypodermis, also known as the subcutaneous layer or tissue, is the deepest and thickest of the three layers of skin, and located right above muscle.

This layer is filled with adipose tissue which is body fat, as well as loose connective tissue containing collagen, and blood vessels which of course, connect to the inside of our bodies.

Here are the main functions of the hypodermis:

- Stores fat: the hypodermis is where fat in the body is actually deposited and stored, and it cushions the inside of our body when we fall or something hits us. Fat in this layer is used as an energy source in times of high stress, like when we fast for long periods of time as an example.

- Helps control body temperature: the fat here also insulates our body, helping to prevent heat loss.

- Attaches the dermis to the rest of the body: the hypodermis has connective tissue that attaches the dermis to muscles and bones. Blood vessels and nerves in the dermis also start to get larger in the hypodermis, where they connect to the rest of the body.

The hypodermis is the source of some issues such as obesity, hypothermia, and aging.

To understand how the hypodermis functions, It's crucial to know about the adipose tissue which largely composes it.

Adipose tissue found in the hypodermis contains a number of important components, which all play a role in its overall function, as well as its connection to the other skin layers with the rest of the body.

Adipose tissue components

There are two different types of adipose, white adipose tissue and brown adipose tissues.

White adipose tissue is the most common, and is useful for insulation and storing energy. It contains numerous types of cells, with adipocytes being the most prominent.

On the flip side, brown adipose tissue produces heat from the food we eat. While mostly found in newborns, It's also found in adults but declines as we age.

Here are important components that are found in adipose tissue within the hypodermis:

- Adipocytes

Adipocytes are a group of fat-storing cells that make up the majority of adipose tissue, and are responsible for accumulating fat in the hypodermis.

This stored fat is used for cushioning, insulating, and as energy reserves. On top of this, adipocytes promote wound healing by recruiting the immune cells—macrophages.

Speaking of immunity, adipocytes contribute to parts of the body's immune system. It does so by producing specific molecules known as adipokines, which work to regulate inflammatory responses.

- Adipokines

Once thought to contain simply lifeless fat, adipocytes produce critically important hormones like leptin, resistin, and adiponectin—which all fall under an umbrella term known as adipokines.

Only more recently has science discovered and begun to understand the role adipokines play in the body. They function as hormones which communicate with other organs like the brain, muscle, the immune system, as well as adipose tissue.

Adipokines serve many different physiological functions in the body, such as regulating inflammatory responses, appetite and satiety or feeling "full", fat distribution, blood pressure, energy metabolism (generating energy from nutrients), and immunity.

The adipokine leptin, for example, tells the body when It's time to stop eating.

Adiponectin, on the other hand, assists in hair growth, sebum production in sebaceous glands, and wound healing by accelerating the growth and migration of keratinocytes to wounds.

Altered levels of adipokines, especially adiponectin and resistin, have been correlated with the severity of inflammatory skin diseases like psoriasis, eczema, and acne.

Adipokines are even specifically stimulated by adipocytes in order to trigger insulin resistance when the body is dealing with high blood sugar and insulin levels, which can lead to type 2 diabetes.

So, crazy enough, type 2 diabetes may partly be caused by an imbalance of adipokines.

How to keep the three layers of skin healthy

We didn't want to just end this article without actually talking about how to keep our skin healthy, did we? When it comes to the health of our skin, the most important thing to keep in mind is simplicity.

Using 10 different products in a daily routine is overboard, and with the multitude of ingredients that come along with this, will likely put your skin in a worse state.

With that in mind, here's how to keep your skin healthy:

1. Daily sunscreen use

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sun exposure causes free radical damage, which are responsible for breaking down collagen and elastin. Continuous free radical damage leads to the premature development of wrinkles, sagging skin, and even dark spots known as hyperpigmentation.

How do we stop this? Sunscreen and sun protection measures.

Use sunscreen that's broad spectrum (provides protection against the broad range of UV light), and minimum SPF 30 but ideally SPF 50.

Here's more information on sunscreens and a list of product recommendations.

2. An effective moisturizer

Many factors can contribute to dry or oily skin, and other skin irregularities and the best thing we can do to keep it hydrated and moisturized is by using an effective moisturizer.

Most moisturizers will really only sit on top of the surface of the skin where they provide their moisturizing properties. This can still be good, but is very temporary, and the reason why your skin might have felt dry just hours after using a product.

The reason for this is because people are used to using water-based moisturizers, and as we've learned from this article, the epidermis essentially acts as a water-repelling brick wall to prevent substances from absorbing into the skin.

Moisturizers containing water can still be effective if they contain certain ingredients like glycerin and low-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid. Unless you're specifically looking for hydration, you might find that a moisturizer containing more oil provides a better moisturizing effect—this typically comes in the form of a cream or oil.

Oil-based moisturizers penetrate into the skin much easier, where they can improve and maintain the skin's barrier function, which in turn will help to prevent TEWL (trans-epidermal water loss). But with that said, you need to use the right kinds of oils on your skin as well.

Oils are usually mainly comprised of two fatty acids: linoleic acid (omega-6) and oleic acid (omega-9). If you remember these fatty acids from earlier, then you know oleic acid in excess isn't good for the skin. It disrupts the skin's barrier function which can lead to breakouts, inflammation, and dryness.

So, you should only use oil-based moisturizers that are low in oleic acid. You can find a list of oils low in oleic acid here.

Here's how you can moisturize your skin:

Botanical Recovery Serum is a moisturizer-serum hybrid that's rich in omega-3 and 6 essential fatty acids, providing long-lasting moisturization.

Botanical Recovery Mask is a leave-on treatment mask, containing all of the critical nutrients for a healthy barrier function: ceramides, cholesterol analog, collagen, and elastin.

What about cleansers? It's important to keep in mind that cleansers are often disruptive to the skin's barrier function by negatively altering the skin's microbiome and surface lipids. Some of the gentlest cleansers available include micellar water, cleansing balms, and oil cleansers.

3. Whole foods, plant-based diet

The reality is that skin care alone isn't enough. We will inherently age to some degree if the diet we consume isn't healthy, and is filled with processed foods.

While about 90% of skin aging does in fact come from sun exposure and environmental factors, a healthy diet helps to naturally protect our skin from these external assaults.

A plant-based diet provides our bodies with an abundance of antioxidants, nutrients, and prebiotics which are crucial for helping to preserve youthful skin.

A lower intake of dairy, processed sugar, and meat with accompanying plant-based vegetable and fruit alternatives are key factors in slowing skin aging.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.